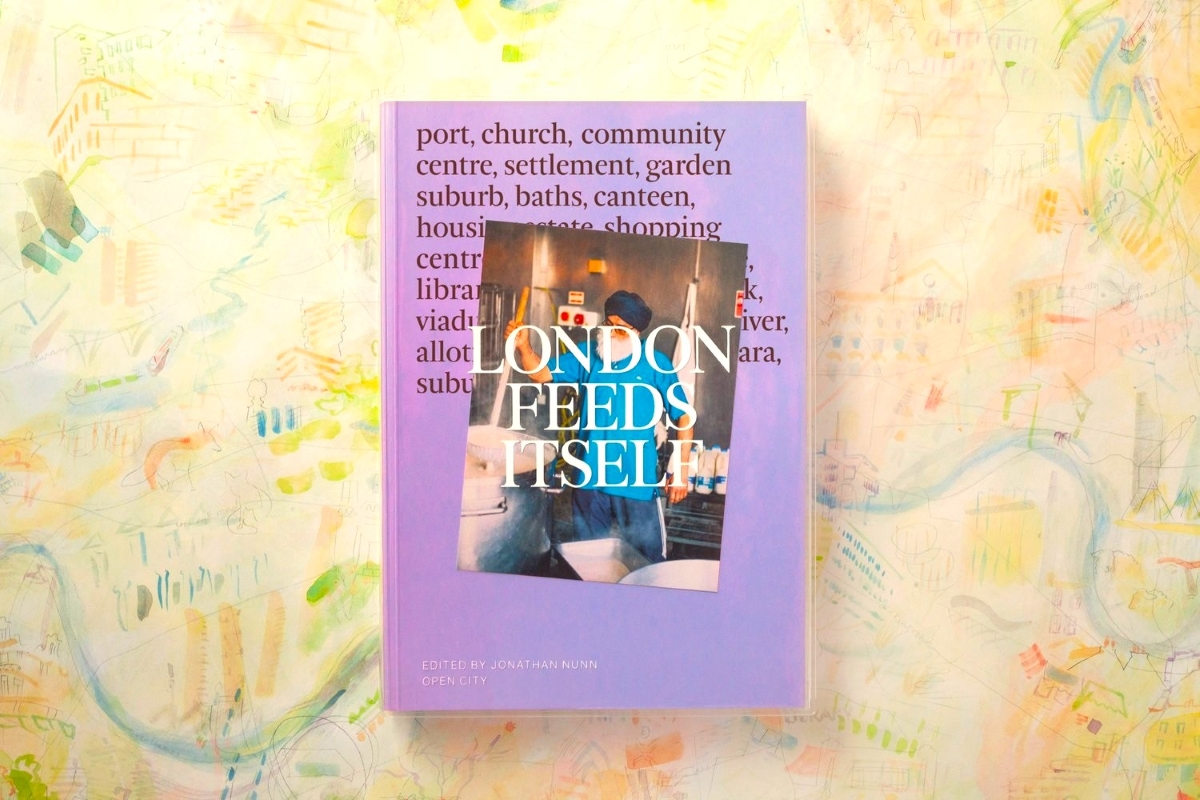

In London Feeds Itself, food writer Jonathan Nunn assembles 25 essays from 25 writers exploring the intersections between food cultures and London’s urban conditions; each chapter delineates the many communities that can be found, seen, and experienced through food. Organisations, families, religion – as it turns out, much of what brings these groups together is a beautiful tapestry of shared daily experiences centred around eating, selling, producing, and distributing food.

From the get-go, the title of this essay collection implies that under the suffocating layer of profits-driven, KPI-chasing, image-conscious food and drinks brands, there lies another world: one where the making and eating of food is also an opportunity to share a moment of peace and connection. For example, Rebecca May Johnson’s essay “The Canteen” beautifully explores our relationship to spaces that nourish both physically and emotionally. Sadly, finding affordable food in a place that won’t pressure you to leave as soon as you’ve purchased something or finished eating is quite a difficult task. Nonetheless, Johnson continues to seek out those spaces where one can buy food that won’t leave you feeling robbed or wretched and instead fill and delight you while encouraging respite.

A through-line of these essays highlights the idea that any place not making a “big return”, even if it is making a marginal profit, is getting squashed, pushed aside, or completely eradicated. In their place, endless Franco Manca’s, Pret A Manger’s, and Côte Brasseries appear, full of identical menus and interiors built for high footfall and returns while encouraging minimal time spent within.

The ever-growing number of identical franchises begets a more significant threat than losing touch with a reality that we’re content with – it lays the groundwork for community spaces and cultural hubs to be quietly destroyed. Yvonne Maxwell describes her unease as the Peckham she grew up in becomes less recognisable every day. The area’s gentrification reeks of modern colonialism, with an entire culture of food, music, and community – one that flourished despite racism and systemic obstacles –once again pushed aside, uprooted, and made unwelcome. Maxwell writes, “Some would simply call this gentrification – the process whereby communities which once survived invasive policing, aggressive stop-and-search campaigns, community centre closures and rising rents succumb to boutique cafes, overpriced restaurants and rooftop bars. But gentrification is to colonialism what orange squash is to an actual orange: it is diluted, pumped with enough of the sweet things to make it palatable.”

London Feeds Itself functions to shine light on places of community and good food in this city. For example, Stephen Buranyi takes us on a journey to the baths of East London, where indulging in a hammam or banya is followed by a selection of salted beef, borscht, or mangal ribs; the steam houses are the attraction, and the food is the result of people coming together and connecting.

Meanwhile, in the essay “The Community Centre”, Jenny Lau takes us to the Hackney Chinese Community Services’ lunch club, a space where elderly Chinese Londoners gather to play mah-jong, talk to each other, and eat a delicious and affordable lunch in an otherwise unremarkable setting. Here, “a hot meal costs £4”, a price tag which is made possible through the planning of menus around weekly donations, Lau writes. “[Plates] of white rice heaped with a variety of stir-fried vegetables, fried fish, and stuffed tofu” were on the menu on this particular occasion, and the reminder that beauty can come from so little is astonishing.

Each piece of writing in this collection not only takes the reader to a different nook or cranny in London but also perks up our sensitivities to the world around us. Rather than having our eyes glued to a phone screen looking for the next exciting food concept store or pop-up with cool branding, these stories allow our natural desires to take over and help us discover different foods and tastes. Suddenly, finding out where food and culture are given the space to exist in this city is an exercise in making notes of where to check out next.

Alongside incredible photography, each essay is accompanied by a related list of alive and vibrant places with great tastes and energy. Lovingly-written descriptions of the sites and food make this book both a practical directory and a beautiful snapshot of London culture frozen in time. Awareness and curiosity are key to finding independent food vendors to support, as the core of what these places set out to do is to sell enough great food to live comfortable lives. In the pages of London Feeds Itself, the city opens up in ways we forgot existed, encouraging you to pay better attention to your surroundings, care more ardently, and smile a little more freely.

You can order London Feeds Itself here.