It takes a lifetime to make the short walk from Vicky’s husband’s money exchange office outside of Seven Sisters tube station to our lunch destination, El Dorado. She must be the most wanted woman alive. Vicky is constantly tackling a barrage of incoming video calls and stopping to hug passersby who cross the road to make contact with her. When we finally sit down, I wade my way through mountainous platos colombianos whilst Vicky eats a yuca soup and tells me she’s always had a soft spot for fairytales with happy endings. But Vicky is not the kind to wait for a floppy haired prince to come to her rescue.

In this story, Pueblito Paisa – Tottenham’s Latin Village – is the princess that needs saving and Vicky and her army are the ones on a fierce, relentless mission to do just that.

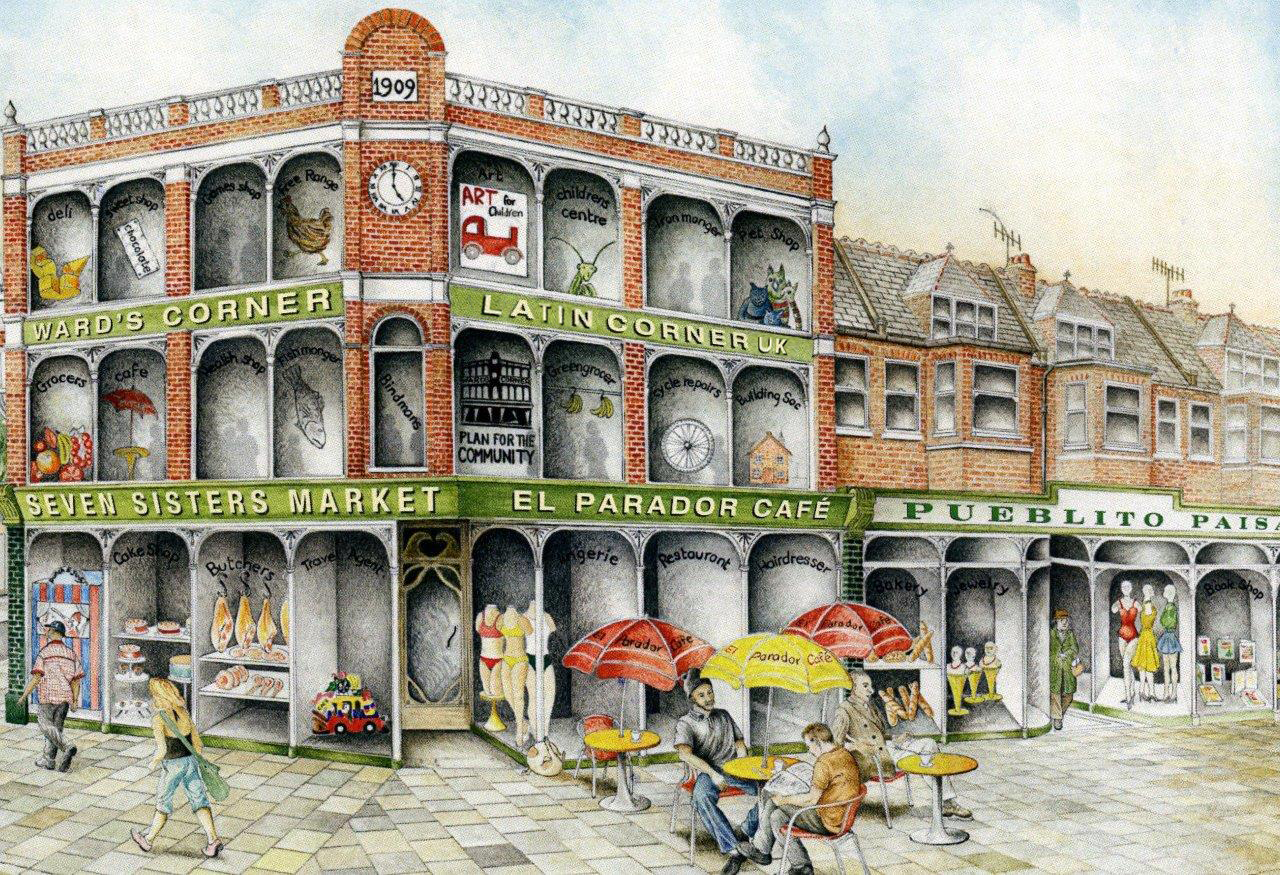

The UK’s only Latin American indoor market – and second-largest Latin quarter after Elephant and Castle – was made up of independent bakeries, nail and hair salons, speciality grocers, butchers and restaurants. There, functionality intersected with pleasure, as children ran freely between the stalls to the backdrop of Cumbia music. But it was shut during the pandemic and has yet to reopen. Despite its closure, many traders have had to start anew at other outlets in the local vicinity. I’m here to visit these restaurants, which we do over the course of three days. El Dorado is the first on the list. It is named after the Colombian legend in which a mythical city in South America is thought to be home to untold riches. The walls are decorated with golden backrests bearing indigenous Quimbayan motifs. There’s a bar where our run of bright pink cocktails is prepared, and ‘piquito’ shots of anise-flavoured aguardiente are poured and slammed.

As we move from our mains to bocadillo beleño, a rectangle of not overly sweet guava jelly, we are in constant conversation with fellow diners. Even though Vicky admits that her unofficial role as community leader can be exhausting, she can’t help herself from wrapping everyone we meet in her impossible warmth and generosity of time. She knows everyone, and they her, which of course all stems from a life spent in the market. It has earned its description as the proverbial ‘village’ for good reason.

But the market’s longevity was threatened long before the pandemic. In 2002, the UK’s biggest private landlord and property developer Grainger PLC set plans in motion to replace it with a slew of so-called “affordable homes” and a flashy new shopping centre. Despite the community’s rejection of multiple planning applications, the development was approved in 2021, helped along by a Compulsory Purchase Order of the site made by Haringey Council.

Like the other approximate 160 market employees, Vicky made her living on a stall in the market since she arrived in the UK from Colombia as a refugee in 1990. The proposed demolition not only threatened her livelihood, but her entire community’s lifeline and sense of identity. “It’s hard to put into words just how important this market is.” She says, “It means everything to me”. As a single mother, it was the market that provided informal childcare, a safety net, friendship and a promise of a new life. Nicolas – a fellow campaigner and trader from Nigeria – calls it the ‘one stop shop’ and the first port of sanctuary where (mainly Colombian) migrants turn up straight from the airport with suitcases in tow. And so Vicky’s call to action began with the very first murmurs of its demolition. She has spent the two decades since devoting everything she’s got to ensure its survival.

The next stop on our journey through the village is Las Delicias de Juancho, which is tucked away in a cosy but inconspicuous corner of a contained unit on the High Road, nestled between a haberdashery, a hair salon and a travel agent called Latin Dreams Travel. The building’s baby pink frontage is offset by the cafe’s deep mahogany interiors. The polished wood shimmers with the steam from my plate of buttery arepa, scrambled egg and sweet, fried plantain and mug of hot chocolate. Juan, the owner of said ‘deliciousness’, takes a minute away from the kitchen to talk with us. He arrived in the UK in 2012 and by “chance and a lot of luck” found a home in the market. He expresses the difficulty of having to start “all over again” after its closure and reestablishing himself in the new premise. He misses market life. Juan talks with such sincerity that Vicky starts to cry. He puts his arm around her with a wide, comforting grin as she performatively wipes away her tears in faux indignation of what he’s caused. Despite Vicky’s insistence, it’s clear there is nothing performative about her tears. She mourns on behalf of all the traders and the life they shared so deeply it can’t be shaken off. Nonetheless, Juan promises that despite its diminutive size, he hopes to accommodate people from all cultures with the same baked goods and cooked meals he prepared in the market. “I will wait for everyone here, until we are able to return to the market.”

The reality of this long-awaited return is becoming increasingly likely. Save Latin Village is one of the most successful UK grassroots campaigns against gentrification, even gathering support from the United Nations Human Rights Council who labelled Grainger’s scheme a “human rights threat”. Thanks to demonstrations, petitions, occupations, and several expensive court hearings, Grainger PLC finally buckled and withdrew their plans on the 8th August 2021. Subsequently, Transport for London – who owns Ward building, which houses the market – have committed to a community-led process to both preserve the market and refurbish the building. Now they are opening a competitive tendering process this summer whereby any groups in the local community can bid on managing the site.

In anticipation of the tendering process to manage the site opening this summer, the campaigns are busy setting up the Wards Corner Community Benefit Society (CBS). It is a new democratic organisation that hopes to restore and manage the Wards Building, and will be wholly owned by its members. Its first interim board has already been appointed and they are getting ready for its first community share issue in the coming months, which will allow the local residents to become members of and own the CBS. “It’s like we’re ‘The Republic Peoples of Tottenham!” Nicholas, a local, quips.

The architecture firm Unit 38 is working with TfL and the council, as well as other partnerships, in co-designing the community informed plan. Vicky says she has noticed a distinct shift in TfL’s attitude in their ongoing discussions, from hostile to cooperative. I emailed Graeme Craig, the Director and Chief Executive of TTL Properties, for comment. He said:

“Seven Sisters Market is a special place in this unique part of London, and we are keen to bring back the community feel and vitality of the original market, while allowing it to operate safely again as soon as possible…We are creating a temporary market space…while we work with traders and Haringey Council to bring forward a long-term solution that ensures the market is able to thrive…”

It is fuelling a new lease of hope for the market’s posterity, so much so that Vicky gushes about her plans to ask Tottenham’s own rags-to-riches pop princess Adele and ‘Queen of Latin music’ Shakira to perform in a reopening fiesta, as we make our way through our restaurant marathon. There is, after all, much to celebrate.

To date, as London’s sprawl widens, the clutch of capital deepens and our expectations of the reasonable price of assets like land and property have shot up. The research project Market4People calls out liberal descriptions of ‘regeneration’ and ‘development’ as an ‘empty lexicon’ that writes over the inevitable displacement and erasure of local residents. The poorest – often immigrant communities – are increasingly absorbed by suburbs that stretch further and further away from the city centre. In this sense, London is what food writer Jonathan Nunn calls an ‘autophagic city’ in the introduction to the book ‘London Feeds Itself’. In a bid to remove unnecessary or dysfunctional components, autophagic cells eat themselves. This biological process has been seen as a response to stress or starvation that can promote a cell’s survival, and at other times, cause the cell’s death. London digests its diet of affordable housing, community hubs, traditional retail markets and green spaces, reemerging as office blocks and luxury flats. It consumes its own vitality, sustaining the survival of some from the death of others.

The historian Devin Smart writes about the ways in which street and market food vendors ensure the reproduction of our city’s economies by feeding urban workers with calories. He describes how the postwar municipal authorities in Mombasa wanted to remake urban society, ridding its undesirable components and ‘informal’ activities like street-food vending. He points out the major contradiction between the elites’ views of the city and the realities of the ways its workers were and are in fact a crucial part of its functioning. Similar ‘empty’ regeneration schemes aim to ‘clean-up’ cities in the UK, scrubbing out the blood, guts and glory of marketplaces like Ridley Road market, along with the Black and Brown bodies that run them. As these places and people fatten up our workforces and stimulate our economy, they are in turn eaten up and spat back out amongst the bulging peripheries. Suddenly, ‘autophagic’ takes on a more monstrous, vampiric sheen.

Latin Village’s resistance is a cause for serious indigestion to these processes. The newly opened restaurants and stalls seemingly ring-fence the periphery of the closed site. Vicky calls them the ‘market guardians’, obstinately gatekeeping whilst it lies dormant. There is something delicious in the ways that by doing so, the village has not only refused closure but in fact spread out further, re-oxygenating Seven Sisters with defiant, Latin life. They evidence the unshakeable synergy between the site and its community. This is a place which plainly exists ‘because of, not in spite of, the urban conditions that surround it’, to further quote Jonathan Nunn’s introductory essay.

This pocket of London is not new, but its reemergence as a newly configured cultural epicentre grown by those that live and work there rather than the dictates of capital is a blueprint for a transformed London. It is one in which wealth is built from the bottom up rather than the top down. It is a space in which marketplaces are everyday vital services and hubs, not experiential and homogeneous simulacrums of such. “Is it too much to ask that residents are in charge of their own destiny?”, Nicholas puts to me quizzically.

In a city that is not short of restaurant closures and intensive regeneration schemes, the community’s 20 year hold onto a singular plot of land is nothing short of miraculous. To participate in this reenvisioning of an alternate capital, go and sample some of the traders turned gatekeepers’ delicious food, whose cooking is gently tending to the campaign’s red hot embers.

Find out more about the Save Latin Village initiative on their website