In Britain, “getting a Chinese” is part of our everyday lexicon, synonymous with easy Friday nights and affordable indulgence. Popping up all over the U.K. between the 1960s and 1980s, Chinese takeaways reached peak popularity by the nineties thanks to an influx of Cantonese immigrants moving to the U.K. post-war. Many made their way by working in the food and hospitality sector, taking over old fish & chip shops, converting them into Chinese takeaways, and introducing a wave of new flavours and textures to the British food scene (albeit modified to suit a milder Western palate).

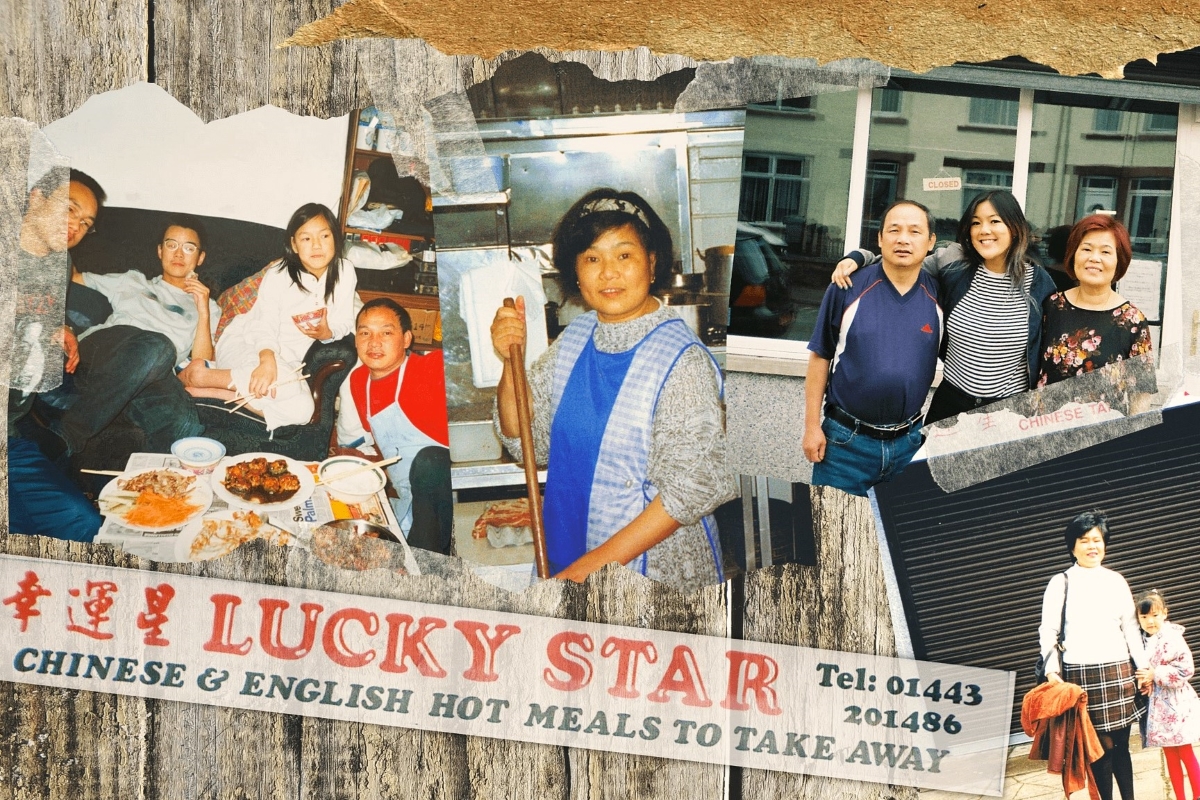

Though a Chinese takeaway has become a quintessentially British sight on any high street, that was not always the case. Angela Hui grew up behind the counter of a takeaway called “Lucky Star” in Beddau, a small town in the valleys of Wales that, being predominantly White, wasn’t particularly welcoming to anyone who wasn’t. Until she moved out into the world for herself, the takeaway was all that Hui had ever known, the force that set the rhythms of her family’s lives. From prepping for service at 5 pm to those busy and sometimes difficult hours of service late into the night, and from working on weekends and holidays to ensuring the kitchen was stocked up on ingredients and equipment, Lucky Star was the beating heart of the Hui household.

In her recently published memoir, Takeaway: Stories From A Childhood Behind The Counter, Hui brings the reader on a journey through her childhood and teenage years, recounting how the relentless, unforgiving nature of her family’s work shaped her. Beyond the pressures of growing up behind the counter of a takeaway, Hui and her family also felt the violence of their neighbours’ racism and xenophobia; ignorant, racist locals would cause trouble, commit acts of arson, and routinely lob insults at the family.

In writing her story, Hui doesn’t shy away from exposing the countless microaggressions, setbacks, and trauma that her parents had to endure to achieve financial security and create a springboard for their children (Hui and her brothers) to receive the education they wanted and live the lives they chose. She writes poignantly, candidly, and without fear, putting an intimate face to the experience of thousands of Chinese immigrants working in the food sector across the U.K.

As recounted in Takeaway, the care and skill that Hui’s parents bring to their craft are awe-inspiring. Set against a backdrop of stress, arguments, and strict standards, Hui unwaveringly holds her parents’ cooking in extremely high regard and, what’s more, takes the opportunity to write evocatively about their food. Her love for it is tangible, through detailed memories of beloved dishes, and Hui closes each chapter with a recipe for one of the dishes featured; this in turn illustrates how intertwined dishes are with her memories. The effect cuts deep. These dishes don’t always come up out of joy or wonder, but are sometimes remembered with a bittersweet taste.

In Chapter 8, “You Ring, We Bring!”, all Hell breaks loose during an incredibly busy night of service. Hui’s father goes too far in an argument with her mother, and at that moment, Hui is forced to act beyond her years, her instincts and anger driving her to protect her mother from her father’s wrath. The next day, in an attempt to smooth over the night’s events, her father makes young Angela’s favourite dish for ‘Family Meal’ (the team meal before service in restaurants): steamed eggs. Taking a dish she loves and offering it up instead of an apology doesn’t have the healing effect that words would, and she finds herself without appetite. Food can be powerful and emotional, but not always in the way we expect or want it to be. This chapter ends with the recipe for the same delicious Chinese Steamed Eggs.

As Angela Hui grows up and begins her life away from the takeaway, she is able to give herself, her needs, and wants more attention. At the same time, her dual identities – Welsh and Chinese – begin not to feel so separate. Before, these two aspects of herself didn’t seem like they could co-exist; the racist comments, the embarrassment of having parents who didn’t speak the language her friends spoke, the pressure to be on call and always available to help out in the shop, and to give back to those who sacrificed everything to offer her a better life. Where before it felt like she had to choose ‘sides’, she now fathomed the possibility of embracing both.

When Hui eventually talked back to her parents, when she chose not to take the takeaway over from them, or when she told her mother about her White boyfriend and the world didn’t end, these accumulated moments helped to bring her peace with everything that made her who she is today. Now one of the most in-demand freelance writers in food, Hui is also the Food and Drinks Editor at Time Out London; she edits REKKI, an app dedicated to helping chefs access ingredients and produce more easily; and she also runs the Instagram account “Chinese Takeaways UK”, which documents different Chinese takeaways throughout the U.K.

By telling her experience growing up behind the counter of a Chinese takeaway in the U.K. in such a detailed, intimate way, Hui’s readers will undoubtedly be left with a newfound appreciation of their humble, local Chinese. Takeaway also evokes respect – respect for Hui’s parents and the thousands like them, for their craft and hardships, for the Chinese diaspora in the U.K. and ultimately, for the author. In sharing her story, Angela Hui has ensured “Takeaway” is more than a memoir; it’s a cultural necessity.

You can buy “Takeaway: Stories From A Childhood Behind The Counter” here, and see more of our Book Club recommendations here.